Breaking Down Barriers to Build a More Diverse Tech Workforce

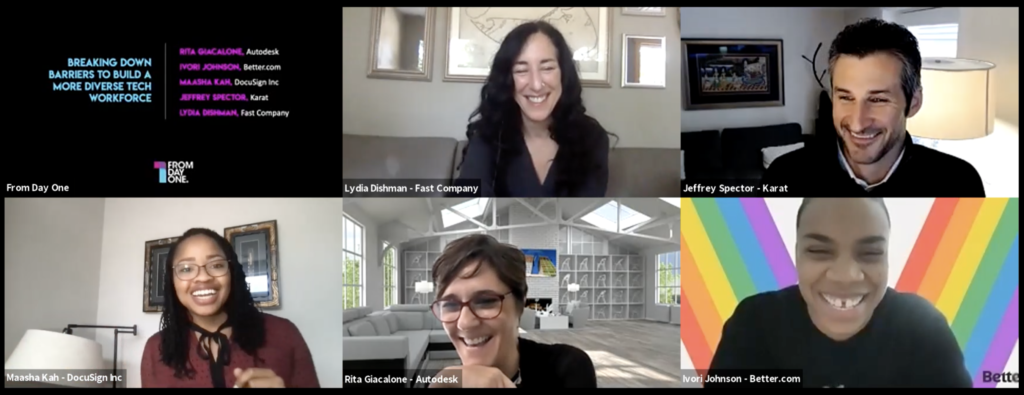

When working as a teacher in Pennsylvania, Maasha Kah realized that systemically, the American education system is geared towards helping people prepare to work–in factories. “We have very rote memorization systems, we ask students to sit up straight, put on a uniform, and fall in line. But we know in the tech industry and in Corporate America in general, innovation is the next wave. We have to be creative,” she said this month at a From Day One webinar, “Breaking Down Barriers to Build a More Diverse Tech Workforce.”

Kah is now the head of talent outreach at DocuSign, the electronic-signature company. In her role there, an integral part of her focus on creativity and innovation is, in her words, how to make diversity real. “I've spent a lot of time dissecting the HR facets of diversity and inclusion,” she said during the panel conversation, moderated by journalist Lydia Dishman. “So I think a lot about how diversity and inclusion are embedded in our HR practices, even when we don't mention them. So there are the verbal things and the processes that we all agree upon–and there are those unwritten, agreed-upon things that just kind of happen. And I find that in those cracks lies inequity.” In the panel conversation, Kah and three other experts weighed in on the topic of hiring for diversity. Their observations:

It's Too Easy to Blame the Pipeline

In recent years, tech companies lacking diversity in their workforces have tended to blame a lack of qualified candidates in the talent pipeline from schools to business. Jeffrey Spector, the co-founder of Karat, a company that conducts technical interviews for companies recruiting software engineers, sees blaming the pipeline as a deflection. “It's an excuse that certain companies make because they haven't hit diversity-hiring goals,” he said. “It affords them the opportunity to not look inward, to figure out like, hey, do we have systemic issues going on? Is there sexism or racism in our processes?”

“I don't think there is truly a pipeline problem,” said Ivori Johnson, senior manager of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) recruiting at Better.com, a digital home-loan corporation. Johnson sees other factors in play. “When we think about the pipeline, we focus on finding the talent and just ensuring that we have more representation at the top of the funnel,” she said. “The problem that exists is if the process itself is inequitable, if our interviews are already screening out people of color, women, or people with disabilities and other communities. Then the problem is within the process,” she continued. “If we are able to fix the process, and we're able to influence hiring managers to get on board, and also train our recruiters to be able to go out and find the talent–and where they can find it–then we will be more successful.”

Rita Giacalone, VP and global head of culture, diversity & belonging at Autodesk, which makes software for 3D design and engineering, offered a broad demographic assessment of the pipeline debate. “Let's take, say, the Black demographic or the Latinx demographic, with the Black demographic being 13% of the U.S. population, Latinx being 18% of the U.S. population, and then let's look at the professional population within these demographic groups,” she said, noting that it's 9% for the Black population and 11% for the Latinx population. “The pipeline problem lies in that delta, and that's systemic in nature. It's in education, it's in access. It's systemic inequity. So the pipeline problem is there.”

Remote Work Widens the Talent Pool, But …

Giacalone enthusiastically reported that her company was recently able to add to its workforce diversity by hiring a candidate to work on a full-time remote basis, which might not have been possible before the pandemic loosened policies about where workers are located. “You're casting a wider net, you're tapping into talent pools that potentially–out of a choice or out of necessity–can't live in very expensive cities,” she said.

Yet the expansion of remote work brings some inequities too, said Kah. “I think the challenge that I would caution–if I could get a bullhorn and just let everybody know, from the mountaintops–is that we have to be thinking about this in terms of being remote-first, versus remote-friendly,” Kah said. She asserted that remote-friendly workplaces have the tendency to create second-class citizens of remote workers by promoting and cultivating the retention of people who are nearest and dearest to the physical office space. “We isolate the office-based leadership.” In contrast, she said, a remote-first policy comes with an inclusive strategy.

Inequities in the Interviewing Process Can Be Remedied

An issue in the technical interviewing process, Spector believes, is lack of professionalism. People conducting the interviews typically are the employees who have the most time to do so, rather than those who are good at it. Another issue lies with access to information on the part of the job candidate. “Everybody should know exactly what the interviewing process is, what competencies you're assessing for,” Spector said. To level the playing field, Karat offers candidates one redo opportunity. “We'll interview again with a different interviewer or a different question,” he said. “And that has huge impacts on underrepresented talent. We see them do much better in the second interview than the first interview, because now they're like, Oh, now I know what the situation is like.”

Similarly, DocuSign gives candidates three different technical questions to answer, each with a different interviewer. “And it's not just based on whether or not you check the box and got it right,” said Kah, “but also your thought process, how you went through the problem, how you were able to explain it, and the way in which you communicated any difficulties and questions that you were able to think through and ask.” This structure helps avoid “a kind of tiebreaker moment,” she said, “where it's like one interviewer says, ‘Yes, this is exactly right. They pass this with flying colors,’ and the other one's like, ‘No, absolutely not, they couldn't figure it out.’”

Confirmation Bias Dies Hard

More inclusivity comes with challenging the traditionally held notion of what “good” looks like. In the recruiting and hiring process, for example, Spector observed a huge bias against active candidates, meaning those who actively searched for the position rather than being referred by someone the company already knows. “Most of the companies we work for, when we start working with them, interview only about 10% of the people who apply actively, and yet those people do just as well on the interviews as the people that they've sourced,” he said. “So we're kind of constantly pushing them” to be more inclusive, he said. “You should go to 20% or 30%, or a bigger percentage of our population who's not in your network.”

A way to get rid of this biased mindset? Johnson suggests starting internally. “If we focus on just trying to recruit as many people from underestimated communities as possible, and we haven't done the work internally, we're just gonna lose them quicker than we hire them,” she said. "So we're starting with educating our employees on: What does diversity mean? What is actually happening in these communities? How can we address our biases and understand what our biases are?” Johnson said. “We're also working with our hiring managers, sharing with them data around where employees are, and what our employee makeup looks like, addressing gaps when it comes to racial and gender diversity, also looking at intersectionality as well, to ensure that our hiring managers are very well-informed, and also our leaders.”

It's also advisable to have a paper trail. "Write everything down!” said Kah. “In DEI, and HR in general, we have this tendency to think of it as fluffy science that's nebulous. We need hard facts, data, and to be able to measure success based on where we come from. We talk about embedding DEI everywhere, but don't know the nuts and bolts. It takes intentional seeds to build the trees that we want."

Angelica Frey is a writer and a translator based in Milan and Brooklyn.

The From Day One Newsletter is a monthly roundup of articles, features, and editorials on innovative ways for companies to forge stronger relationships with their employees, customers, and communities.